What is JavaScript Event Loop Anyway?

If you have been working with JavaScript for long enough, you must have heard about the event loop, might have gotten curious about it and might have watched the legendary Youtube video of Philip Roberts on event loop or the one by Jake Archibald and learned about it or never got the hang of it or forgot what you learned in the first place. You should also check out this great video by Lydia Hallie. All of those helped me understand what event loop is, and it’s my personal note for future references, if you find any issues, please feel free to open a Github issues.

It’s an important concept to understand if you want to write effective JavaScript programs in JavaScript. Interesting bit, event loop is not part of the language, it’s rather part of the JavaScript run time.

Before writing more about the event loop, let me introduce to you two important data structures, stack and queue.

- Stack : A stack is a linear data structure that adheres to the Last In, First Out (LIFO) principle.

- Queue: A queue is a linear data structure that operates on the principle of First In, First Out (FIFO).

With that out of the way, another important thing to know of is the call stack.

With all of this out of the way, let’s learn about event loop.

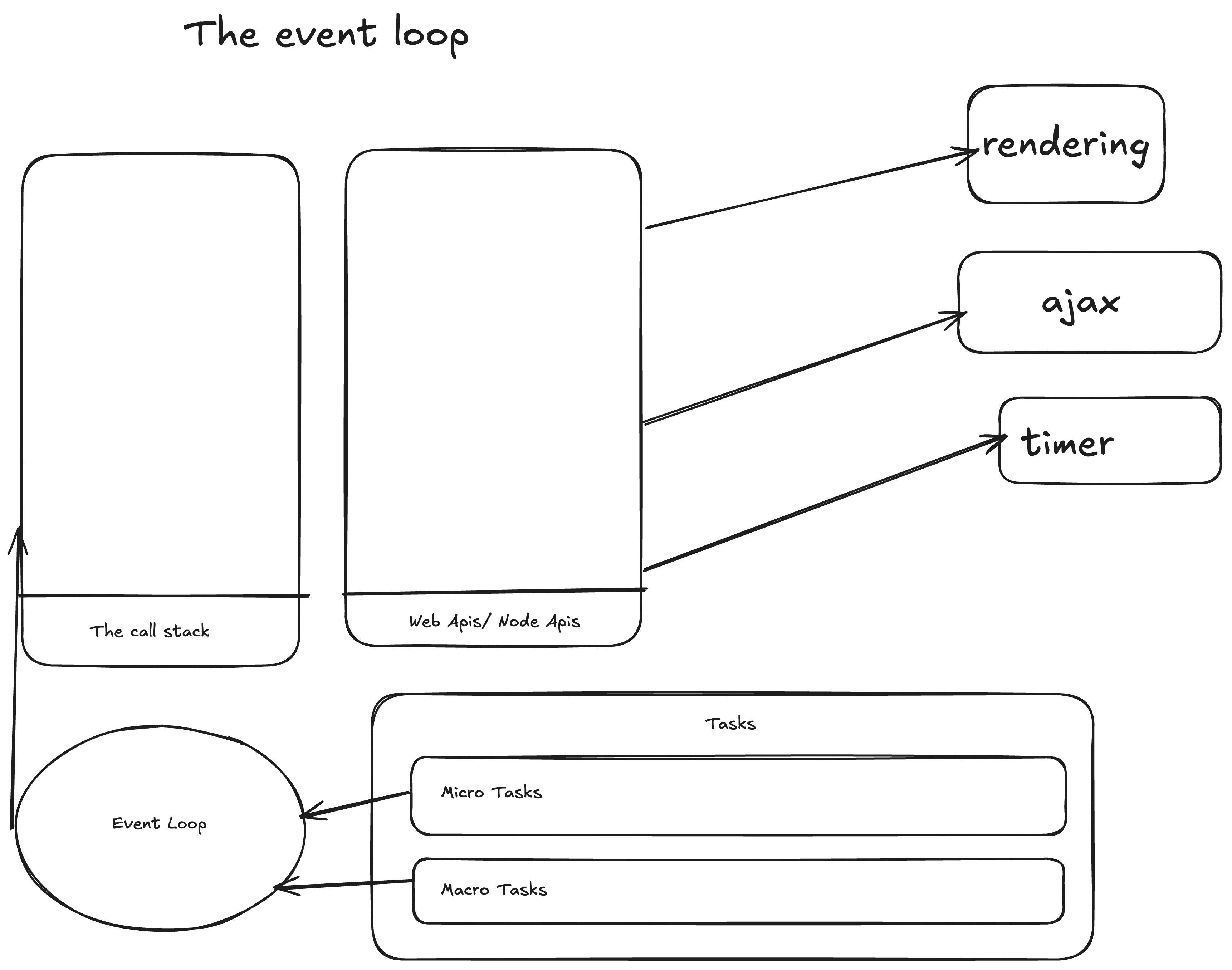

What is the Event Loop?

Event loop is a mechanism implemented by the browser’s JavaScript engine/runtime for chrome it’s V8, for Mozilla it’s Spidermonkey.

To understand what event loop does within the JavaScript run time, we need to understand few concepts and their relations with event loop.

Core Components

- Call Stack: Have you ever seen a call stack overflow error? It happens when we create an infinite loop, for those who are familiar with React, might have seen this when they tried to use

useEffectto update a state which performs a re-render thus running theuseEffectagain and again, till the browser decides to crash the page and we get “Maximum call stack size exceeded” error. Call stack as the name implies follows the stack data structure, it’s Last In First Out. Call stack is where things happen in JavaScript, it runs frame by frame from top to bottom, only one thing can run here at once. - Web/Host APIS: How the browser works under the hood is quite complex bit of engineering, For the sake of this article, I am trying to simplify things, as I myself even don’t completely understand what goes under the hood of a browser. For our need, we need to know, the JavaScript run time(v8/spidermonkey) doesn’t use call stack for everything, they use the native codes for things like “setTimeout”, “setImmediate”(node.js), “fetch” and “DOM events”, once the host environment done running the native API, it moves the callback to the queue.

- Queues:

- Micro Task Queue: It gets precedence over Macro Task Queue, it follows the FIFO principal. Anything from

Promise.then/catch/finally,MutationObserver,await functionsgets queued to micro task queue. You can also push a task to micro task queue usingqueueMicrotask. Micro tasks themselves can spawn new micro tasks, as it has precedence over macro tasks and render queues, It’s very much possible to block the call stack just by using micro tasks. The event loop will not move to Macro task queues till it ensures the micro task queue is empty, so it’s important to keep in mind while writing programs and not to block the call stack with micro tasks. - Macro Task Queue: It’s also known as the task queue, Things callback from web apis are pushed to Macro task queue. That’s why it’s also known as callback queue. Example

setTimeout,setImmediate, callback from these gets queued to the task queue from where the event loop pushes it to the call stack.

- Micro Task Queue: It gets precedence over Macro Task Queue, it follows the FIFO principal. Anything from

- Render Queues: Even though it happens in between Micro task and Macro task, I am putting it at last because I wanted to group the task queues together. Render queues are not queues like those other queues, It’s part of the browser’s rendering pipeline. The browser tries to perform re-render every 60fps(approximately every 16.67 ms). The render pipeline consist of these steps, 1. requestAnimationFrame callback, 2. style calculation, 3. Layout reflow 4. Paint and 5. Composite, you can do a browser rendering by using

requestAnimationframe, it is recommended to use for animation instead of the old animation hack likesetInterval(animateSomething, 1000 / 60), forcing to re-render at 60fps, it doesn’t work consistently, but if we userequestAnimationframeall dom changes made in a callback of requestAnimationframe will be painted together, layout will feel smooth, there won’t be any layout thrashing.

How It All Works Together

The EVENT Loop: So what’s the event loop’s job in all of this, to say it bluntly or simply, event loops only job is to make sure the task queues are empty. Then again how it gets items pushed onto it, we already know the host environment’s native API’s callbacks gets pushed to the queue, Promises also gets pushed to the queue, so how does that happen.

The fundamental rule is: Microtasks → Rendering → One Macrotask → Repeat

Examples in Action

- Promise Example: As I have already mentioned the call stack executes code frame by frame from top to bottom. For example it encounters a code like this

const p = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

resolve(42);

});

p

.then(result => console.log(result))

.catch(e => console.error(e))

.finally(() => console.log('promise done')) When the call stack comes across this code, it handles the Promise body immediately resolves it, but it doesn’t run anything after then, it pushes it to the micro task queue. And the event loop moves the queued task out of the queue and push it to the call stack and then we get “42” on browser’s console.

Let’s see another example

const p = fetch('/data.json'); // returns a *pending* promise

p.then(res => console.log('B', res.ok)); So what happens when the call stack comes across this bit of code?

- The fetch is a browser api, so it hands over this to the browser and fetch api returns a promise

- Then the call stack comes across

.then, executes and registers a reaction(something that will happen in future), we still don’t get to the callback of then. - When the browser’s network layer done executing the fetch the js runtime fulfils the promise and moves the callback to the micro task queue

- The event loop moves the task from the micro task queue to the call stack where we get the output(console.log(’B’, true))

- It’s a very simplified version of how this happens

- Callback Example: Callback example is a bit simpler to understand, let’s also do this with code

console.log('A');

setTimeout(() => {

console.log('C');

}, 0);

console.log('B');Guess what will be the output? even without a deeper knowledge most JavaScript devs should be able to answer this. It’s

A

B

CLet’s see how the call stack interprets this line by line,

When it comes across “console.log(’A’)”, it’s immediately get executed by the run time.

Then it sees a setTimeout, it’s a browser’s native API, it hands over the responsibility to browser’s time API.

It then goes to the next chunk of code and it’s also get’s executed immediately by the JavaScript run time and we get “B” on the console.

When the native API done with setTimeout, it pushes the call back to macro task queue, and the event loop moves it from the queue to the call stack and here we get console.log(’C’)

- requestAnimationframe example:

console.log('1: Synchronous');

setTimeout(() => console.log('4: Macro task'), 0);

Promise.resolve().then(() => console.log('2: Micro task'));

requestAnimationFrame(() => console.log('3: requestAnimationFrame'));

console.log('1.5: Synchronous');

// Output:

// 1: Synchronous

// 1.5: Synchronous

// 2: Micro task

// 3: requestAnimationFrame

// 4: Macro taskFrom the example, you can see browser performs a render in between Micro Task and Macro Task, hence the output of requestAnimationFrame is in between.

That’s pretty much how it works, any callback within our code gets moved to the queue to be moved to the call stack later, hence keeping the call stack free and only using when needed.

- Execution Order Example:

console.log('1');

setTimeout(() => console.log('4: Macro task'), 0);

Promise.resolve().then(() => console.log('3: Micro task'));

console.log('2');

// Output: 1, 2, 3: Micro task, 4: Macro task

// Microtasks (Promise) execute before macro tasks (setTimeout)Conclusion

That’s the very simplification of what the event loop does, according to the MDN docs on JavaScript run time, the event loop is the queue, whose ultimate goal in life is to make itself empty till it dies or the tab/page/browser closes. I think of it a Call stack or the main execution stack’s sidekick, it helps moving things smoothly in the browser or other JavaScript run time environment. Understanding this process helps developers reason about execution order, debug tricky async issues, and write programs that feel fast and fluid. In practice, the event loop is what allows JavaScript to handle asynchronous tasks efficiently, making it a cornerstone of modern web development.